The Netwerk Oorlogsbronnen Effect

Posted on 12/05/2021 by Peter Tessel

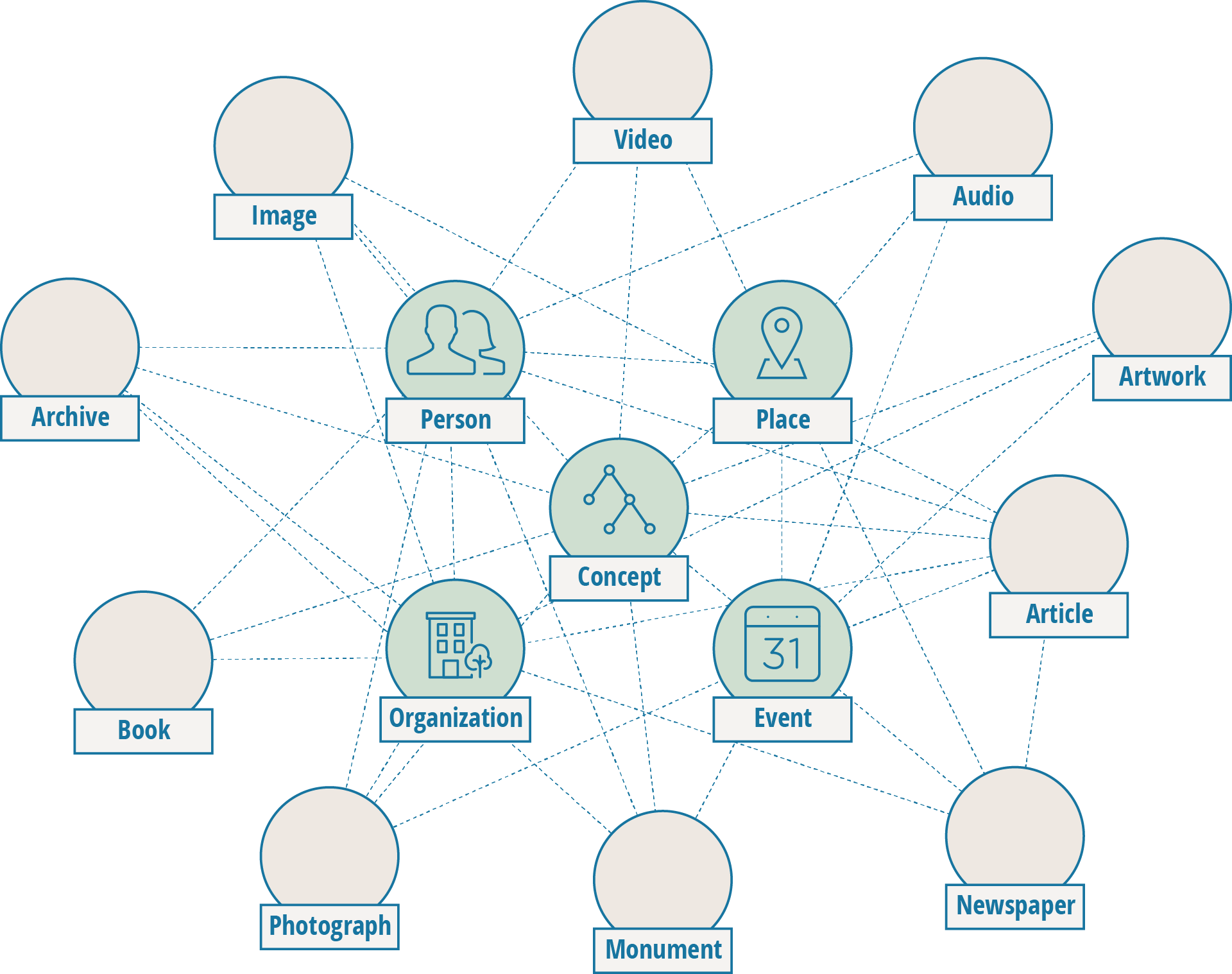

Our long time client Dutch Network War Collections, in Dutch: Netwerk Oorlogsbronnen (NOB), uses Spinque Desk to connect the dispersed collections of hundreds of archival institutions, museums, memorial centers and libraries at home and abroad. They link the containing photos, objects, letters, records, diaries, posters, newspaper reports, film images etc. to its thesauri on persons, places, concepts, organizations and events. Via its websites the NOB gives access to this knowledge graph on the Netherlands in the Second World War.

In an effort to enable its users to piece together as complete a picture as possible about their research topics, the NOB is continuously adding additional pieces of information to its knowledge base. Currently it links the heritage of 250 organizations with around 200 remaining.

In the process of connecting new collections the NOB has to comply with the GDPR's privacy and security requirements which means it needs the consent of the persons whose data they are collecting and using. The consent of living persons, that is, since data related to the deceased are not considered personal data in most cases under the GDPR. The problem, however, is that administrators often do not know if the persons in their collections are still alive. Usually their collections cover only a small part of a person's life. For example, the records of a camp only state when a person entered it and when s/he left again. If the person did not die in the camp, it cannot be inferred whether someone is still alive.

In recent years the NOB has solved this problem by developing so-called matching skills. Using Spinque Desk it matches the personal data of organizations that potentially want to participate with its own data on the persons concerned in order to determine whether someone is still alive. In this way the NOB helps prospective participants to map out the risks involved with sharing their datasets. Some participants do not want to take any privacy risks while others want to open up their archives as much as possible in order to serve specific target groups well. Using their matching skills the NOB enables all participants to share (parts of) their collections in the way they think is most appropriate. For example, it enabled the City Archives of Rotterdam to share the relevant parts of its archive on detainees during the war. Not only Jews, people in hiding and resistance fighters were arrested in this period but also thieves, black traders and prostitutes. The latter groups of people were filtered out of the detainees archive in order to protect their privacy, regardless of whether they were dead or alive.

However the nice, and unforeseen, thing is that the matching skills also work the other way round. While they were creating the richest possible data source for their various users, the NOB created a service that enables participants to enrich their own data at the same time. For example the City Archives of Amsterdam had a local labor administration (40.000 cards) and transport lists on men who were forced to work in Germany during the war. They knew little else about these men and asked the NOB what additional information they might have about them. The NOB connected the labor cards to the transport lists, matched them to their own data on the persons concerned and identified a few thousand men that died in Germany while forced to work here.

One of them was Willem Stevens who was 15 when the war started and who was called to work in Germany three years later when he had just turned 19.

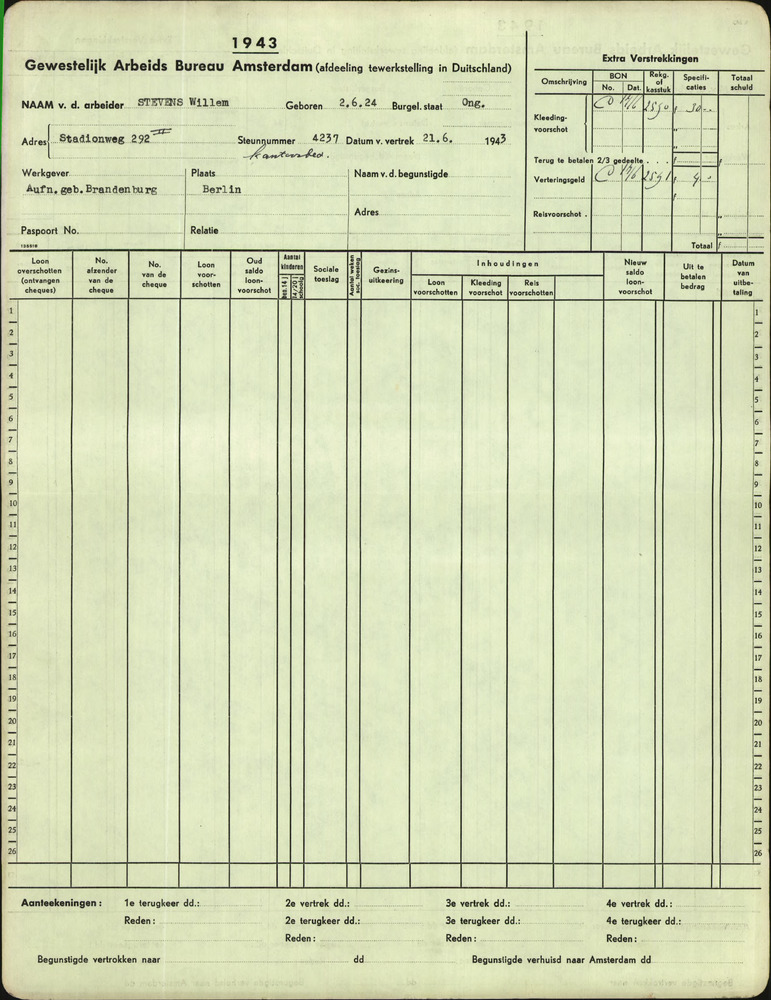

labor card of Willem Stevens

On the 17th of June 1943 Willem Stevens requested a passport...

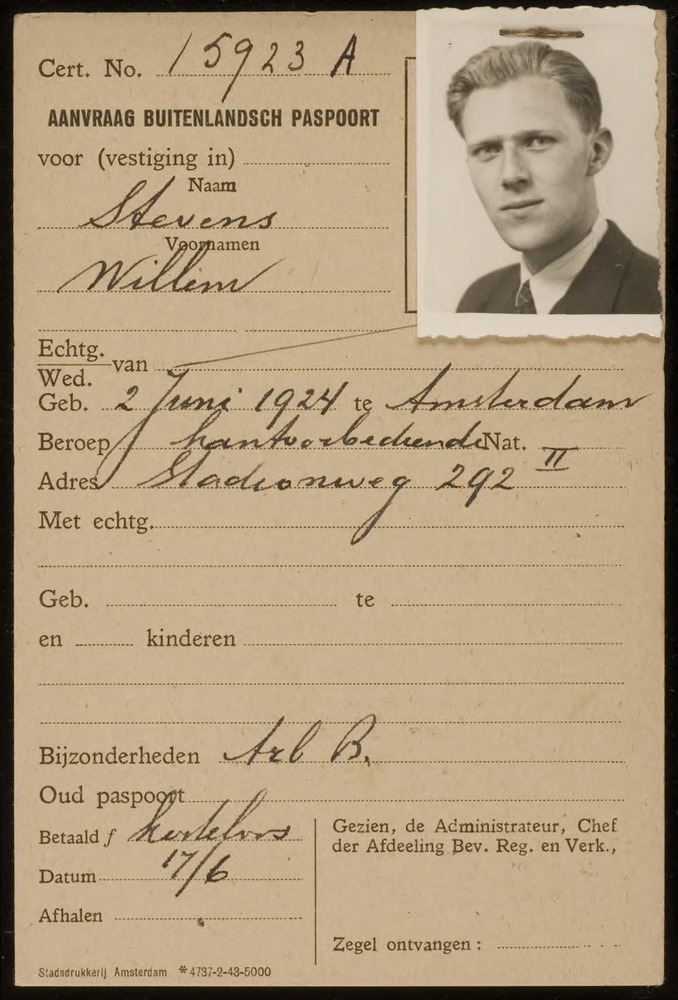

application for passport by Willem Stevens

... and on the 21st of June 1943 he was transported to Berlin.

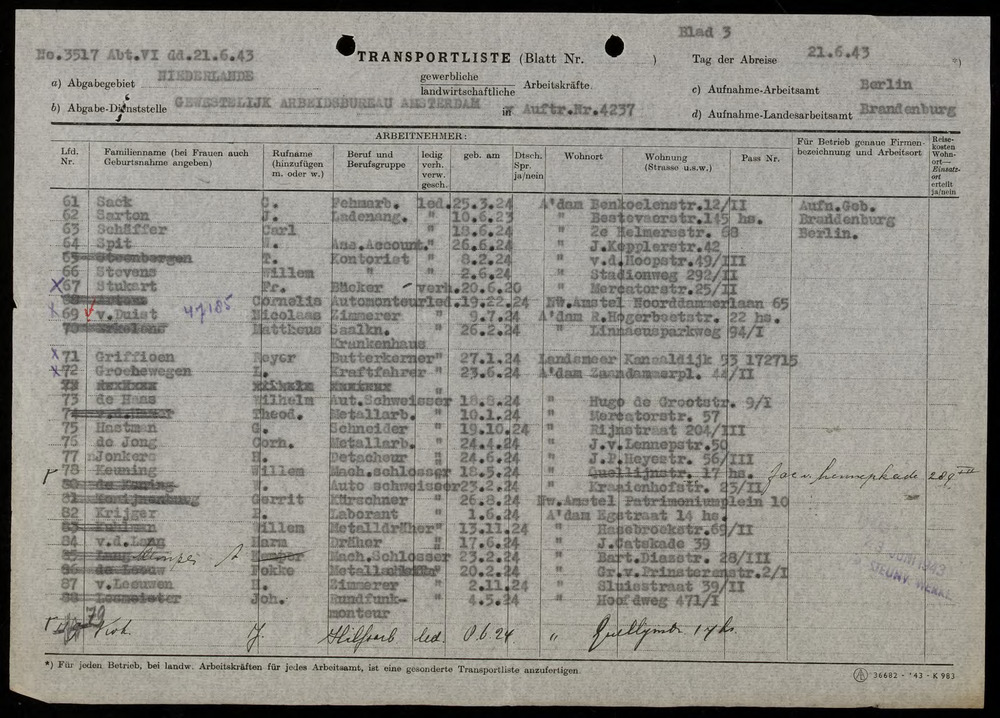

list of the transport Willem Stevens was on

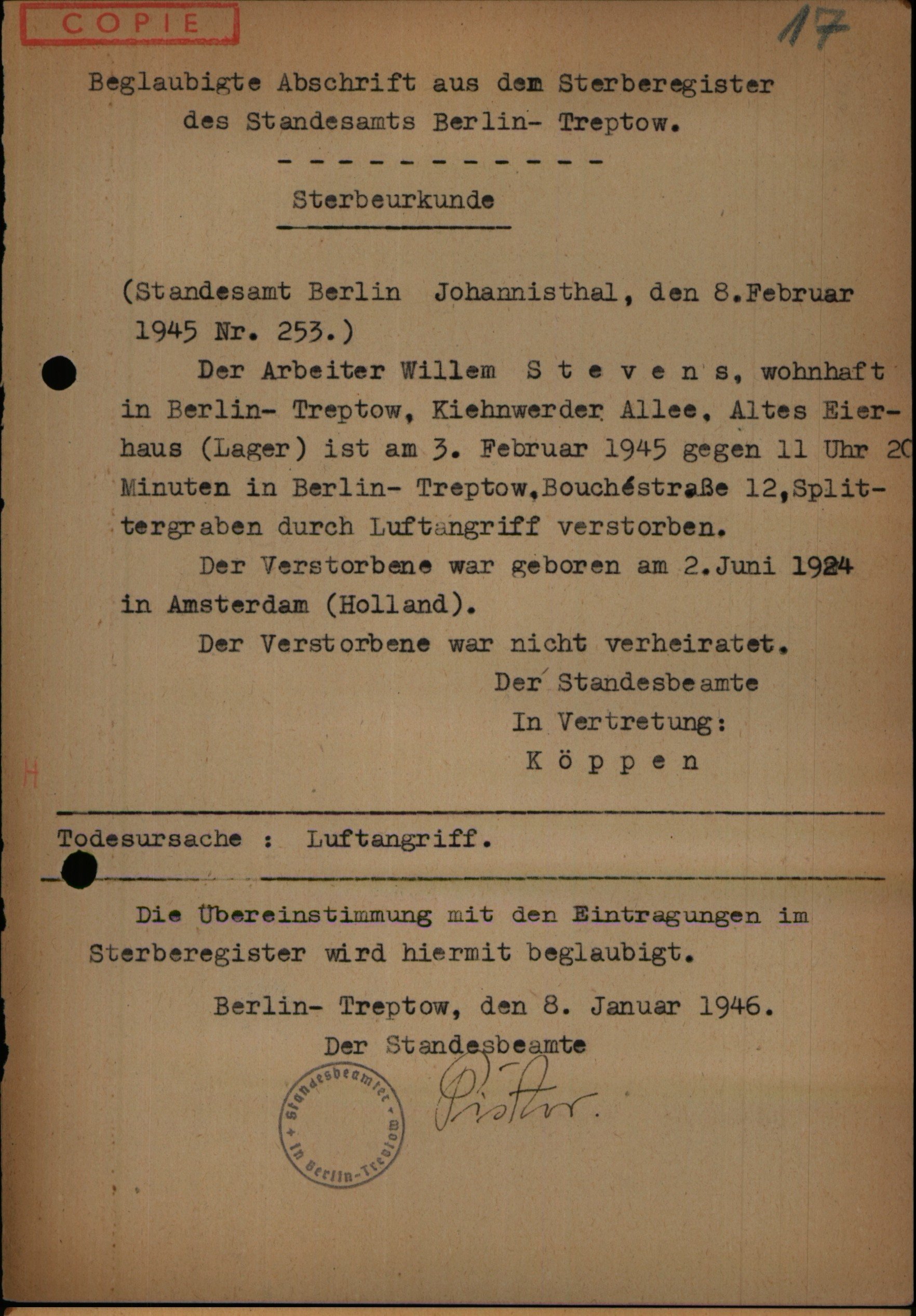

Here the trail of the City Archives came to an end. Another participant in the NOB had previously provided data that told what happened to Willem Stevens while he was in Germany. The CBG|Center for family history has a German death certificate in her archive stating that Willem Stevens died more than a year and a half later in Berlin during an air raid:

death certificate of Willem Stevens

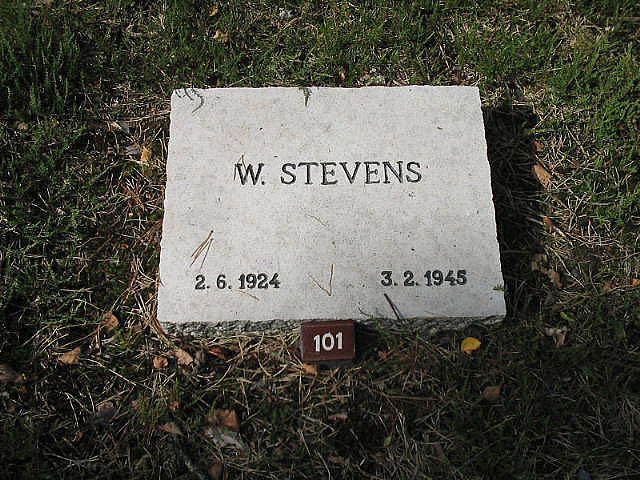

The Dutch War Graves Foundation, another participant in the network, finally had a picture of Willem Stevens' grave on the National Field of Honor in Loenen where he was reburied after the war:

grave of Willem Stevens

All this information is publicly available on the internet and the city archives could have found all this itself, but for 40,000 men this would have been unworkable. Using the matching skills, the NOB can perform these kinds of tasks automatically and researchers can focus on follow-up research of a different order: where were the forced laborers employed, what percentage died in Germany and what was the cause of their death?

By connecting ever more collections the NOB is not only able to present its users an ever more complete picture of the Netherlands during the Second World War but also to enrich the collections of its participants with data from other collections. A good example of the Netwerk Oorlogsbronnen effect ;)